The importance of context

In other sections of the website, we have emphasised the importance we attach to as much information as possible about the site and context in which the pieces were found. For this reason, we would like to devote this section to briefly mentioning a number of cases which help to illustrate that in this type of study it is not possible to reduce the interest to certain formal aspects and to ignore the data relating to the provenance of weights, balances, etc. In fact, the usual examination of the material from which the object under study was made, its weight and dimensions, duly combined with the location and characteristics of the find, is what can provide a solid and conclusive assessment.

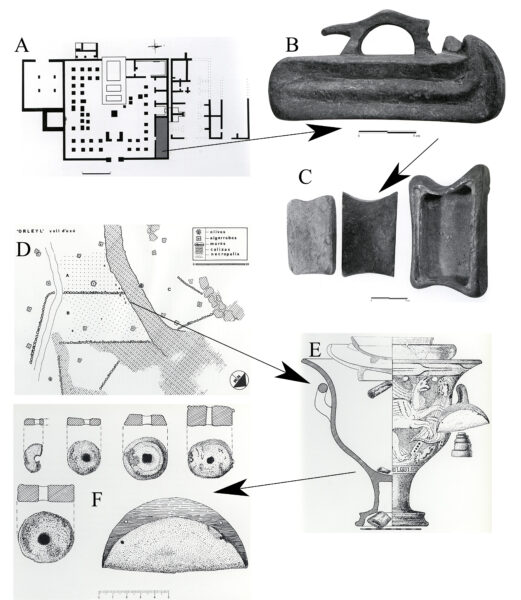

Fig. 1. A) Plan of the forum and the macellum of Arucci, with the Sala de los Aediles in shadow; B) Decempondium found at Arucci; C) Detail of the decempond found at Arucci; D) Plan of the Orleyl I necrópolis; E) Materials found in grave II of the Orleyl I necrópolis; F) Weighty remains found in grave II of the Orleyl I necropolis (A-C after Bermejo and Campos, 2009: 190, fig. 5; 192, fig. 7 and 190, fig. 8. D-F after Lazaro et alii, 1981: 10, fig. 2; 37, fig. 17 and 33, fig. 14).

Fig. 1. A) Plan of the forum and the macellum of Arucci, with the Sala de los Aediles in shadow; B) Decempondium found at Arucci; C) Detail of the decempond found at Arucci; D) Plan of the Orleyl I necrópolis; E) Materials found in grave II of the Orleyl I necrópolis; F) Weighty remains found in grave II of the Orleyl I necropolis (A-C after Bermejo and Campos, 2009: 190, fig. 5; 192, fig. 7 and 190, fig. 8. D-F after Lazaro et alii, 1981: 10, fig. 2; 37, fig. 17 and 33, fig. 14).

For the pre-Roman period, for example, there is the case of El Oral (San Fulgencio, Alicante), where different phases of excavation have documented a large structure identified as a “prominent dwelling”, consisting of a central courtyard and rooms distributed around it. In one of these rooms, interpreted as an andron due to its dimensions, location and flooring, a cylindrical lead weight was found, along with ceramic material that dates the context to the 6th-5th centuries BC. A bronze scale was also found in an adjacent room (Abad and Sala, 1993: 85-86 and 228, Abad et alii, 2001: 165-166). Everything seems to indicate that the use of these weighing objects here is linked to a certain socio-economic status.

In a similar sense, the discovery in what has been identified as the officina ponderaria Aruccitana (Aroche, Huelva), located in a room near the forum of this Huelva locality (Bermejo and Campos, 2009: 190-194). In the Sala de los Aediles, who, according to the lex Irnitana (19 and 84), were responsible for the control of weights and measures in Roman cities, a sealed bronze box containing a lead ingot, marked with an X indicating its value, and a small figurative bronze counterweight, was found under a high level of spoliation and collapse.

However, there are other sites on the Iberian peninsula where the ponderal objects come from a commercial context, as is the case in ancient Malaca (Málaga), specifically on the site of the current Picasso Museum. The excavations revealed a street close to the wall where, among the structures documented, some rooms paved with crushed earth and coloured clay stand out, interpreted as tabernae, next to the old Punic anchorage and a possible metallurgical workshop. In this environment, dated to the end of the 3rd century BC, six cubic weights have been documented, whose function could be related to the trade of the tabernae or to the manufacture of metal objects (Mora, 2011: 175).

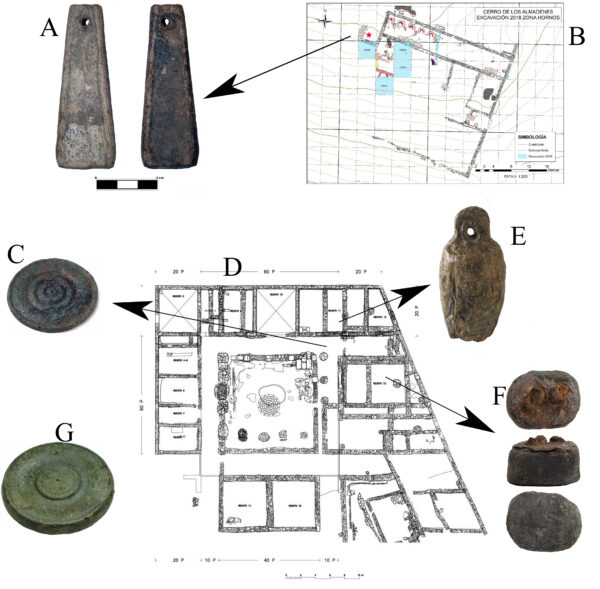

The numerous objects found in different rooms of the macellum at Iruña-Veleia (Iruña de Oca, Álava) date from the imperial period. Some weights date from the Flavian period or the 2nd century AD, but there are also some from the end of the 3rd century or the 4th century AD, demonstrating the longevity of their use (Aurrecoechea-Fernández, 2021: 7-8).

Fig. 2. A) Lead weight found in the Cerro de los Almadenes; B) Plan of Sector II of Cerro de los Almadenes, in red where the ponderal was found; C) Lead discoidal ponderal found in Iruña-Veleia; D) Plan of the macellum from Iruña-Veleia; E) Cylindrical lead counterweight found in Iruña-Veleia; F) Rectangular lead counterweight found in Iruña-Veleia; G) Disc-shaped lead weight found in Iruña-Veleia (A-B after Barrios and Monco, 2021: 23, fig. 3 and 22, fig. 2; C, E-G after from Aurrecoechea-Fernández, 2021: 7, fig. 8; 6, fig. 6; 11, fig. 14 and 16, fig. 12; D after Reinares, 2021: 19, fig. 16).

Fig. 2. A) Lead weight found in the Cerro de los Almadenes; B) Plan of Sector II of Cerro de los Almadenes, in red where the ponderal was found; C) Lead discoidal ponderal found in Iruña-Veleia; D) Plan of the macellum from Iruña-Veleia; E) Cylindrical lead counterweight found in Iruña-Veleia; F) Rectangular lead counterweight found in Iruña-Veleia; G) Disc-shaped lead weight found in Iruña-Veleia (A-B after Barrios and Monco, 2021: 23, fig. 3 and 22, fig. 2; C, E-G after from Aurrecoechea-Fernández, 2021: 7, fig. 8; 6, fig. 6; 11, fig. 14 and 16, fig. 12; D after Reinares, 2021: 19, fig. 16).

This type of object is also frequently found in mining sites, both pre-Roman and Roman. An example of this is La Loba (Fuenteobejuna, Cordoba), where more than a dozen examples have been documented, all made of lead and of different typologies, from different rooms of the metallurgical mining complex (Blázquez et alii, 2002: 350-352).

The ponderal found in the Cerro de los Almadenes (Otero de Herreros, Segovia) is also made of lead and has a truncated pyramidal shape. This case, which dates back to the imperial period, is again associated with a mining context (Barrios and Moncó, 2021), where the specimen was documented in a room next to a battery of furnaces, in the collapsed layer of the walls that delimit the room.

Lastly, we refer to the presence of ponderal objects in funerary contexts, where they were deposited with an obvious symbolic value. Among the cases from the pre-Roman period, we have chosen the find from the necropolis of Orleyl I (Vall d’Uxo, Castellón) because we consider it to be particularly significant. In spite of the fact that it was excavated in 1962 and that it had been severely damaged by agricultural work, 5 truncated conical and disc-shaped lead weights were found in burial II. The set of weights accompanied a burial gift consisting of a weighing pan, three attic jars and three inscribed weights (Lázaro et al., 1981: 34). It is precisely the presence of the inscribed weights that has made it possible to link this tomb to a possible merchant named Bododas (Lázaro et alii, 1981: 32-38), for whom a notable economic status has been proposed (Melchor et alii, 2010: 41-42).

Another example of weights found in a funerary context is the northern necropolis of Balsa (Torre d’Ares, Faro), where three bronze weights, two spherical and one rectangular, dated between the first and third centuries AD, were found in the ancient excavations carried out by Estácio da Veiga (Pereira, 2014: 75-78 and 188). It is true that on this occasion, the lack of a rigorous archaeological methodology makes it difficult to identify the precise location of the find, but it is nevertheless another case in which the weight objects with a clear symbolic value were deposited in a funerary context.